Exploring Italy’s Linguistic Diversity: A Journey through the Dialects of the Country

Modern Italian dialects all stem from Vulgar Latin, the spoken form of Latin widely used across the Roman Empire. Vulgar Latin likely had its own local peculiarities before Roman rule fell, yet its remnants persisted even into modern day Italy until unification occurred in 1848 with Classical Latin being studied globally instead of its various variants being developed as separate tongues; consequently many dialects are incomprehensible with one another today.

As political unification of the peninsula and travel and relocation took place, so too did the need for a national language become ever more pressing. Florentine literary language fulfilled this need thanks to aggressive education programs; today it’s used throughout Italy for law, business and education purposes while dialects remain restricted mainly for home use and among close neighbors in urban neighborhoods or villages.

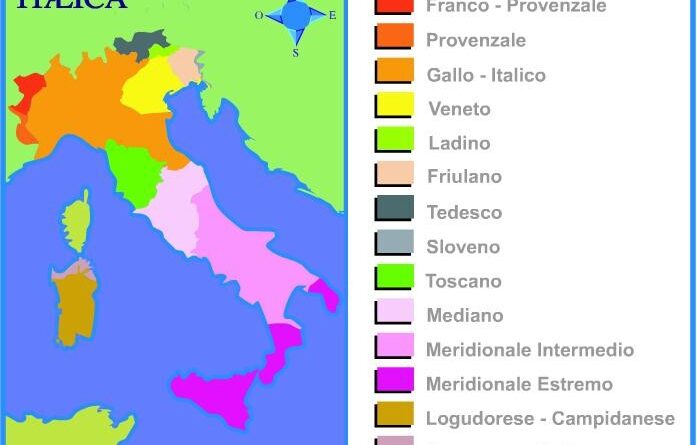

Italian dialects fall into two broad groups, not including Sardinian which is considered its own language entirely. These two groups can be distinguished by a line known as the Spezia-Rimini Line that runs east-west across the peninsula following mostly Tuscany-Emilia-Romagna borders before cutting through Marches; above this divide lie Northern (Settentrionale) dialects while below lie Central-Southern (Centro-Meridionale).

Septentrional or Northern dialects can be divided into two main groups. Geographically speaking, the Gallo-Italic group encompasses regions like Liguria, Piedmont, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna along with parts of Trentino-Alto Adige; its name derives from Gauls who once inhabited this part of Italy who left remnants of their Celtic speech behind in modern dialects. Next largest is Venetic; its boundaries loosely follow Veneto region boundaries.

Central-Meridional dialects fall into four distinct groups. The Tuscan group covers an area roughly equivalent to Tuscany. Latin-Umbrian-Marchegian dialects span from northern half of Latium (including Rome) through most of Umbria and some Marches to form a collective known as Latin-Umbrian-Marchegian; sometimes collectively referred to as Central dialects; these may also sometimes be combined. Directly below them lie Meridional dialects that come in two varieties; Intermediate Meridional dialects cover most of southern Lazio, Abruzzi Molise Campania Basilicata parts while Sicily delines Extreme Meridionals that delineated Extreme Meridionals that exist separately from their counterparts on either end.

Italy contains two other Romance languages within its borders. Ladino, spoken in Friulia and Dolomite mountains of northeast Italy, can be divided into Friulian type in Friulia and Dolomitic type spoken on Dolomite mountains; Sardinian (spoken on Sardinia island) can be further broken down into Logudorese-Campidanese and Sassarese-Gallurese varieties for further information; see Sardinian Language and Culture Page).

Dialects of Italian are also spoken beyond Italy’s physical borders. Istrian dialects are restricted to southwestern Istria Peninsula in modern day Croatia and constitute Septentrional type dialects; Venetic spoken further north are of Central-Meridional type while Corsican spoken on Corsica falls under Central-Meridional type dialects.

Characteristics of Urban Dialects

Milanese can be classified as a Septentrional dialect within Gallo-Italic subgrouping. As in German and French, its front vowels of o and u can be found: fok (fuoco), kor (cuore), and brut (brutto).

Venetian, like Milanese, belongs to the Septentrional dialect family; however it belongs to another sub-group: Venetic. Venetian differs from Milanese in not possessing “gallic” vowels such as o and u; this may make Venetian more similar to Tuscan dialects found further south. Verb xe can serve in third person instead of the standard verbs like e (is) and sono (are), while double consonants tend to become singularized: el galo (il gallo) and letto (il letto); note also use of masculine article el (il).

Florence Florentine dialects, including Tuscan dialects like Florentine, are some of the most conservative Italian dialects. An example of their conservatism can be seen by their retention of consonant cluster -nd- as seen in Quando; most dialects level this cluster to -nn-, like quanno. Modern standard Italian is also influenced by Florentine literature written by Dante and Petrarch; however, Florentine differs slightly in some regards from Standard Italian due to local dialect differences. At its heart lies the “gorgia Toscana”, an intricate pattern of aspirated stops thought to have its source in Etruscan phonology. This throaty aspiration produces sounds similar to Greek chi or German ch, similar to raspy English h. This results in words such as chasa for casa (house), ficho for fico (fig); similarly aspirated vowels appear before medial T: andatho or andaho (andato), datho or daho (dato).

Rome offers many distinct differences from standard Italian. Most notably, Romanesco features several deviations: for instance, -nd is often dropped to create quanno (quando), monno (mondo). Furthermore, standard gl (similar to English million), is rendered as j (pronounced like English y), in vojo (voglio); maja (maglia). We may also encounter substitution of r for l in certain instances: for instance in “er core (il cuore); vorta (volta).

Napoletano, the Neapolitan dialect, is well-known outside the standard Italian due to its extensive use in popular Italian songs. This meridional dialect features initial “chi-” instead of pi-; such as in “chiu (piu), and “chiove (piove). Final vowels without accented vowels often sound similar to an English schwa; articles (excepting “ll'”) in Napoletano are reduced to single vowel forms: ‘o libbro (il libro), “a casa (la casa), ‘e piatte (i piatti).