Italian Emigration: Tracing the Journey of Italians Abroad

Since 1861, over 24 million Italians have left Italy since unification; that figure amounts to almost one third of Italy’s entire population at that time!

At first, this exodus affected all Italian regions; between 1876 and 1900 however, it primarily affected Veneto, Friuli Venezia Giulia and Piedmont.

Over the subsequent two decades, migration records shifted towards southern regions; an estimated three million people left Calabria, Campania and Sicily alone.

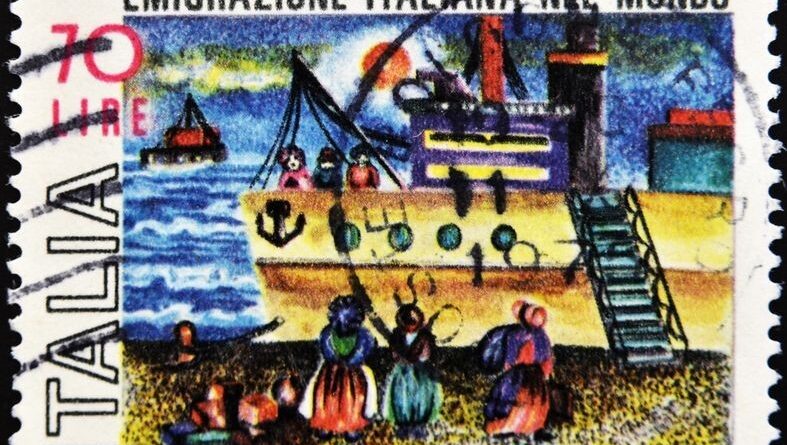

Many ships carried millions of people on their voyages across continents in search of fortune and opportunity abroad. People sold what little possessions they owned to embark, hoping that fortune lay ahead abroad.

After 1870, small Italian shipping fleets were supported with subsidies from the Kingdom of Italy Government.

Reasons that drove millions to leave South Italy were many.

As part of Piedmontese invasion of Kingdom of Two Sicilies (carried out without formal declaration of war) in 1860, machinery from southern factories was brought northward where Piedmont, Lombardy and Liguria industries would later emerge.

Southern Italy had been devastated by a war claiming over one million lives, natural catastrophes, taxes, oppression by feudal-style rulers and oppressive tax regimes that left no choice for its population but to migrate en masse. Due to hereditary land ownership being determined by politics and economic power based upon land ownership alone – giving only poor classes little chance at improving their condition through political or social reform.

After 1870, population growth resulted in continental migration up until 1895; thereafter transoceanic migration surged.

About 1880 there were approximately 109,000 annual emigrants; by 1900 that figure had increased to approximately 311,000; 1913 saw nearly 873,000. After World War One emigration resumed with force; reaching 615 thousand units by 1920 before it finally stopped due to fascist regime’s restrictions on migration in 1927.

Between 1876 and 1925, over 9 million Italians left Europe, including seasonal emigrants or those who departed the peninsula while remaining on continent.

Italian emigrants overwhelmingly chose the United States, Argentina and Brazil as their destinations of emigration.

Since 1880, when their capitalist development kicked into gear, the United States have opened their borders to immigration; ships transported goods across Europe and back with new residents; since ship prices were generally less expensive than train travel costs in Northern Europe, millions chose to cross over.

Between 1880 and 1915, four million Italian emigrants settled in the United States; out of an estimated total of 9 million who made the crossing across the Ocean to Americas. Most came from Southern Italy.

Arriving in America was often met with harsh medical and administrative checks, particularly at Ellis Island – known for being known as “The Isle of Tears”. Even today, in New York’s Museum of Emigration there are suitcases full of poor clothing belonging to those arriving from Italy.

American industrial production increased between 1850 and 1900 at an astonishing rate, and Italian immigrants who arrived with an average daily wage of $8 were essential components in its development. Unskilled workers from Southern Italy contributed significantly to building railways and North American roads while working mines, often for average daily wages that rarely exceeded two dollars.

Emigrants were predominantly poor and illiterate peasants and laborers who left their cities and towns due to unemployment and hunger.

Emigration was seen favorably by Italy’s government, yet nothing was done to assist or protect emigrants. The reasoning for this favorable stance came from an assumption that any money sent home by emigrants could help address long-standing issues in Italy’s South as well as other depressed regions on its mainland peninsula.

Since 1931 there had been an abrupt decrease in emigration. This could be attributed to two sources; firstly the United States of America which restricted immigration admissions; then also to fascist governments which curbed it further abroad; as well as Italy’s fascist government halting it altogether during World War 2. During WWII even further arrest of migration occurred as Italian citizens residing abroad were considered political enemies to fight; the second wave of migration which started immediately following WWII continued from 1946 until 1971 and saw entire generations of workers leaving Europe; as it did at first with World War 2.