Italian Heraldry, Nobility, and Genealogy: Unveiling Ancestral Lineage in Italy

As yet, only limited works have been published in English on Italian heraldry, nobility and onomatology as related to genealogy research. Yet all three fields depend upon such genealogical research for success. This concise presentation should serve not as a historical treatise but as an easy guide for those curious about these subjects.

Heraldry (Italian: araldica) refers to the study of coats of arms. Historically, however, this term referred to royal court officers responsible for keeping records of these coats of arms and titles of nobility – heralds. Although such officers remain attached to royal households in the UK and Spain, Italy abolished its monarchy in 1946. Nobiliary titles and coats of arms are no longer recognized by the government of Italy but their use remains legal; some private organizations, including Corpo della Nobilta Italiana and Sovereign Military Order of Malta recognize nobiliary titles such as these (though such recognition requires extensive genealogical proof of patrilineal nobility).

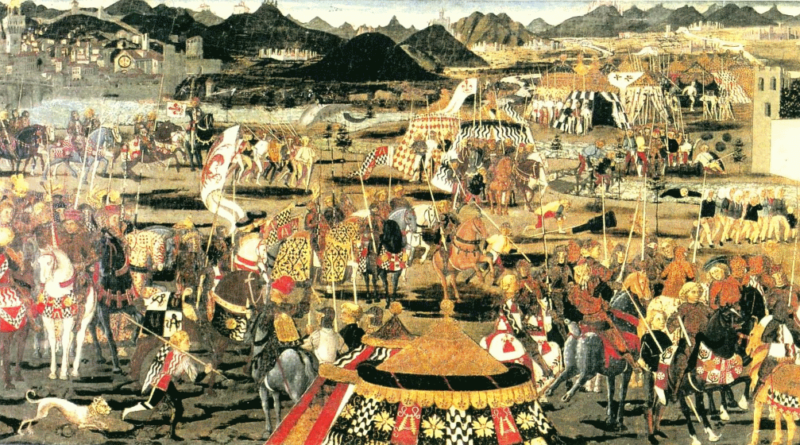

At the heart of the twelfth century, when Italy was under Norman rule, coats of arms emerged as distinctive insigna on shields worn by knights and other nobleman. Combatants were easily able to recognize a fully armored knight wearing a helmet by their colorful shield design, which also appeared on their surcoat – thus giving rise to the term “coat of arms.” Over time, certain blazons and feudal titles (count, baron etc) passed from father to son. As these insigna and titles belong to particular families, it should go without saying that unrelated families that share surnames like Ferrar, Rosso, Smith or Jones cannot claim these coats of arms or titles of nobility as their own merely due to sharing the same surname – such as Mr. Johnson of Wales claiming the estate of Mr. Johnson from New York because both share his surname.

History makes clear the hereditary nature of coats of arms and titles of nobility, becoming more evident through time. Heraldry is so closely intertwined with genealogy that stemma (Italian for coat of arms) is also Latin for “family tree.” Coats of arms in most countries (such as Italy) serve as indications of nobility (i.e. hereditary aristocracy); genealogical research can provide proof for this fact.

Unfortunately, various genealogical research firms in Italy and elsewhere have duped thousands of clients into believing they possess genuine coats of arms or titles of nobility. To bolster their fraud schemes, genealogical institutes in Florence – specifically two highly-respected genealogical agencies – often cite historical sources as well as family ties associated with their products or services to add credibility. These “official” documents often turn out to be little more than expensive fantasies for customers who believe they deserve coats of arms, yet fall prey to fraudsters who sell these bogus documents (often generation after generation!). Italians who think they have entitlement to coats of arms typically become victims. Unfortunately, many fraudsters have long since since been making such promises!

Some family historians create for themselves (or their ancestors) coats of arms or aristocratic lines from research done at public libraries, often with no connection whatsoever between themselves or their ancestors and ancient dynasties bearing similar surnames – such as Medici, Este, Grimaldi Visconti Savoia. Such researchers likely share no more than just their surname with those he claims as history, yet thousands of ordinary families hold famous surnames such as these today – many sharing such names alongside ancient dynasties bearing similar surnames without being related or related to any ancient dynasties with which these same surnames.

Onomatology, or the study of proper name origins, should be approached with extreme care. Any native Italian speaker would know that Ferraro comes from blacksmith while Rosso means redhead; similarly obvious are the origins of toponymic names (Veneziano, Calabrese and Milano). However, the origin of less frequent surnames may depend on their region’s dialect – in other words, one surname could have one set of origins in Sicily but another in Piedmont. Assuming no knowledge of their family’s regional origins, researchers may attribute Piedmontese origins to Sicilian surnames or vice versa. Given that Piedmontese differs significantly from Sicilian, onomatologies may vary significantly; onomatology research is more accurate when knowing this detail; most firms conduct such investigations without this knowledge and some authors assign flawed onomatologies to certain surnames.

Onomastic conclusions regarding patronymic surnames can often be inaccurate. The surname Di Cesare for instance, derives from its ancient Latin root Caesar, yet this has no relationship to how Italian families today use this surname; these individuals likely descend from medieval ancestors who gave themselves Cesare as given name, rather than descended from one of Rome’s Julian emperors or any of France’s Bourbon kings – similarly not all Frenchmen named Louis are descended from them either!

Heraldic, nobiliary and onomastic knowledge relies heavily upon genealogy; an objective approach to these subjects can make a distinction between actual family history and make-believe family folklore.